Alabama in the early 1960s wasn’t the easiest place for an African-American woman to raise 10 children, but Algia Benjamin’s mother did just that—until they left for Boston in 1966. Growing up during the Civil Rights movement when segregation was still in place, Benjamin remembers his mother being so afraid that she sometimes felt reluctant to take them out on trips. As he points out, those were the days when a black man couldn’t pass a white woman on the sidewalk without being expected to move aside. It’s no surprise his mother is the person he most admires in life.

“My mother had 10 children and held it all together,” he says. “She made sure we had a roof over our heads and food in our stomachs.”

The strong example Benjamin received from his mother is what inspires him to offer the same support to his 14-year-old daughter. Knowing that the stress of financial insecurity can prevent people enjoying the good things in life, he wants his daughter to be free of that worry. Therefore, he works seven days a week selling Spare Change News.

He says, “If people don’t have that financial burden, people are able to focus on happiness more.”

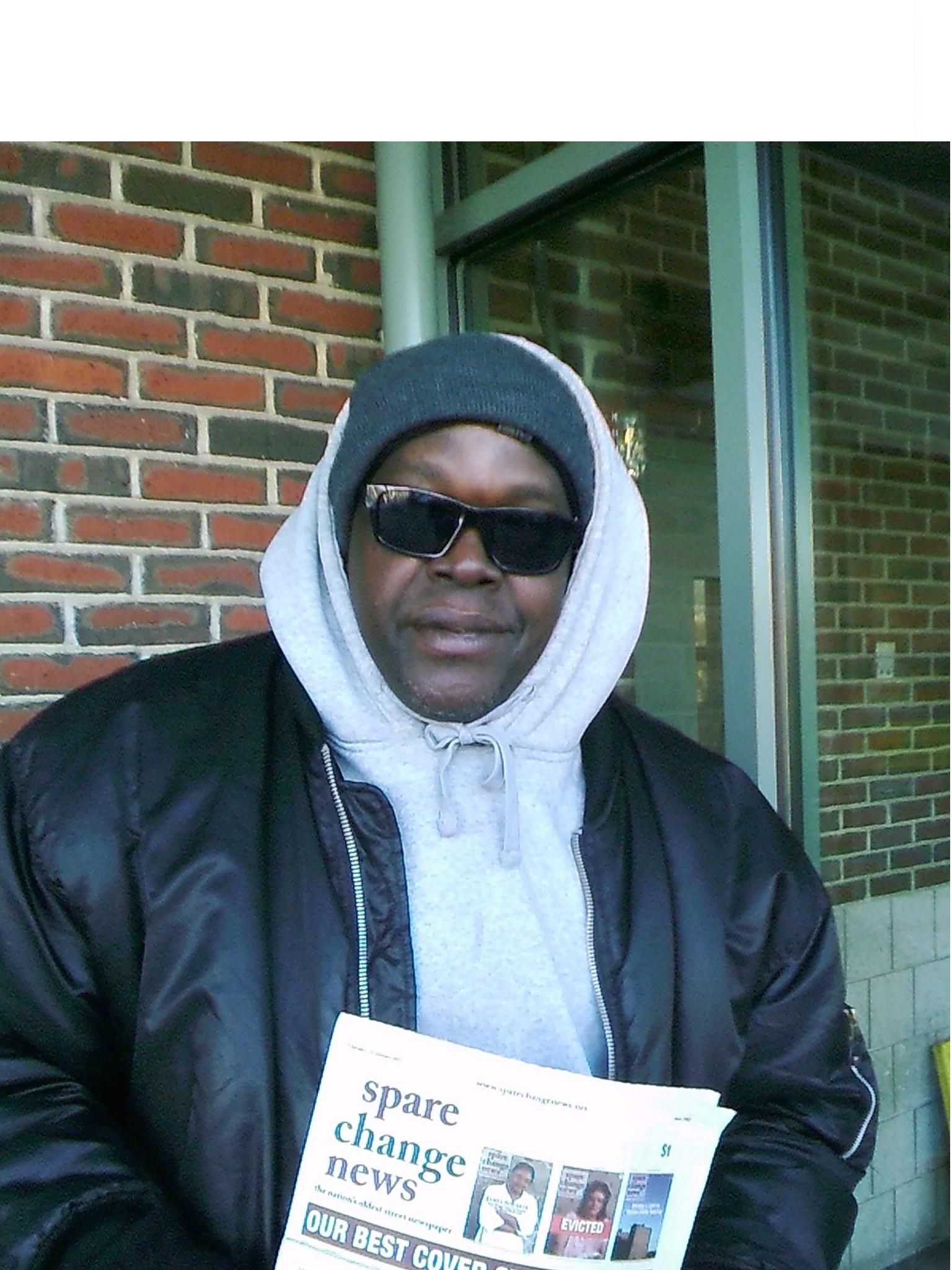

Benjamin has been selling Spare Change News for 22 years, making him one of the paper’s most experienced vendors. In fact, he started selling the paper just three months after the publication was founded. Since Spare Changes News is America’s oldest street newspaper, Benjamin must be one of America’s longest-serving street vendors.

I met him on a freezing Tuesday afternoon outside CVS in Porter Square. Whereas other vendors prefer to stay warm by selling their papers in train stations, Benjamin likes it outside. The perks of working as a vendor include meeting lots of people. He sees about 40 people regularly in Porter Square and many of them have become friends and acquaintances, especially the ones who stop for a chat: as he says, he “can’t talk to a moving target.”

Sometimes, he says, he feels “like a street psychologist. I value being able to communicate well. People talk to me about everything under the sun.”

Halfway through our conversation, Benjamin mentions the recent events in Ferguson, Missouri, where communities came together to protest the killing of Michael Brown, an unarmed black teenager, by a white policeman. Benjamin is no stranger to racial profiling: a few weeks ago, when he was returning from his mother’s house in Cambridge, he was stopped by a police officer who said he matched the description of a recent suspect. Rather than being made to feel safe by the very officers who are appointed to protect us, Benjamin, at times, feels wary. Countless African-American men throughout the nation could tell a similar story, he says.

On a more hopeful note, Benjamin is pleased by how “all communities, all people who’ve experienced discrimination,” came together to protest the legal system’s treatment of the deaths of Michael Brown and Eric Garner.

I asked Benjamin who his heroes are. Although he says he doesn’t have “heroes” as such, there are some men he looks up to, particularly those African Americans who’ve succeeded in academia—men like Cornel West (he sat in one of his classes), Henry Louis Gates and Julius Wilson.

“I’m fascinated by African-American people who’ve achieved the impossible,” he elaborates. “People who’ve become professors.”

Benjamin’s wisdom clearly comes from a mixture of study and hard-earned experience, but he also derives understanding from the Hope Fellowship Church on Beech Street in Cambridge. Since he spends a lot of the week working, it’s helpful to be reminded of what’s most important in life.

I wrap up the interview asking Benjamin when and where he’s happiest.

He leaves me with the following words to live by: “When I open my eyes in the morning and I can look out and see the sun shining upon my face. God has given me another day—another day to become a better person.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.