One of Joe M.’s earliest memories is of jumping into bed at night and his mother saying, “Quiet, I’m praying.” Joe always respected his mother. Telling me about her now, he laughs at the little quirks in her character—for instance, the fact that she would always make Joe and his sisters go to church on Sunday but she would stay at home. Every evening, before she went to sleep, she would pray for all the people in her life, he says.

His father was a less soothing influence. When he was six years old, Joe woke up one day to learn that his father’s gambling habit had cost the family their home and they would be moving into a shelter in Boston. On top of the gambling, his father was abusive. Years later, when he was dying of throat cancer, he asked Joe to forgive him and Joe did, willingly.

“When he was ready to die, he asked me if I’d forgive him,” Joe recalls. “I’m grateful I did. It’s helped me not to hate anybody.”

One of the benefits of having a veteran for a father was that the family didn’t stay homeless long and were offered public housing in Cambridge. Around that time, Joe was put in the “special class” at school because he couldn’t “catch up with the other kids.” At 16, he quit school and his mother told him he was never going to learn anything. Within a year, he was washing dishes at Al and Tony’s, an Italian restaurant on Harvard Street in Brookline, and his mother had died.

Addiction and faith are recurring themes in Joe’s life. With a father who suffered from a severe addiction, it’s not surprising that Joe himself developed one too. For him, it was alcohol. He remembers looking out his window one day—sometime in the 1980s—and seeing a man in handcuffs being led away by the police. His first thought was that he could be that man. Going down on his knees, he asked God to keep him away from alcohol, and now he’s been sober for 29 years.

As well as spending 22 years as a pick-up truck driver for the City of Cambridge—“cleaning up Harvard Square,” as he puts it—Joe has spent much of his life studying the Bible and has taken many people to Bible study classes. It wasn’t until 1991, however, that he was baptized; he describes the ceremony as making him feel like “a new person coming up out of the water.”

At one point in our conversation, he pulls out a handful of letters and photographs. Each one seemingly represents a person he holds dear. I see the name “Stephanie” scrawled on a yellow envelope. He tells me it belongs to a “Christian girl” he was involved with once, a Jewish convert to Christianity who encouraged him to return to the Church at a time when he was moving away from it.

“She called me up and told me to come back,” he recalls. When Stephanie expressed a desire to move to New York for a job, he let her go and the relationship ended. “I didn’t want to stop her going. That’s up to her,” he says.

Next to the envelope is a photograph of Joe standing next to a smiling, blond-haired, young man. It’s his brother, Phil, who died in 1997 and whose picture he carries next to the others in his backpack. Perhaps prompted by his leafing through these old letters and photographs, more memories come flooding back: he tells me about Millie and Madeleine, his stepdaughters, whom he lived with in the late 1970s, a time he counts as among the happiest in his life. Though the marriage to their mother didn’t last, Joe doesn’t linger on regret.

“We had our ups and downs,” he says, “but I think about the good things we had.”

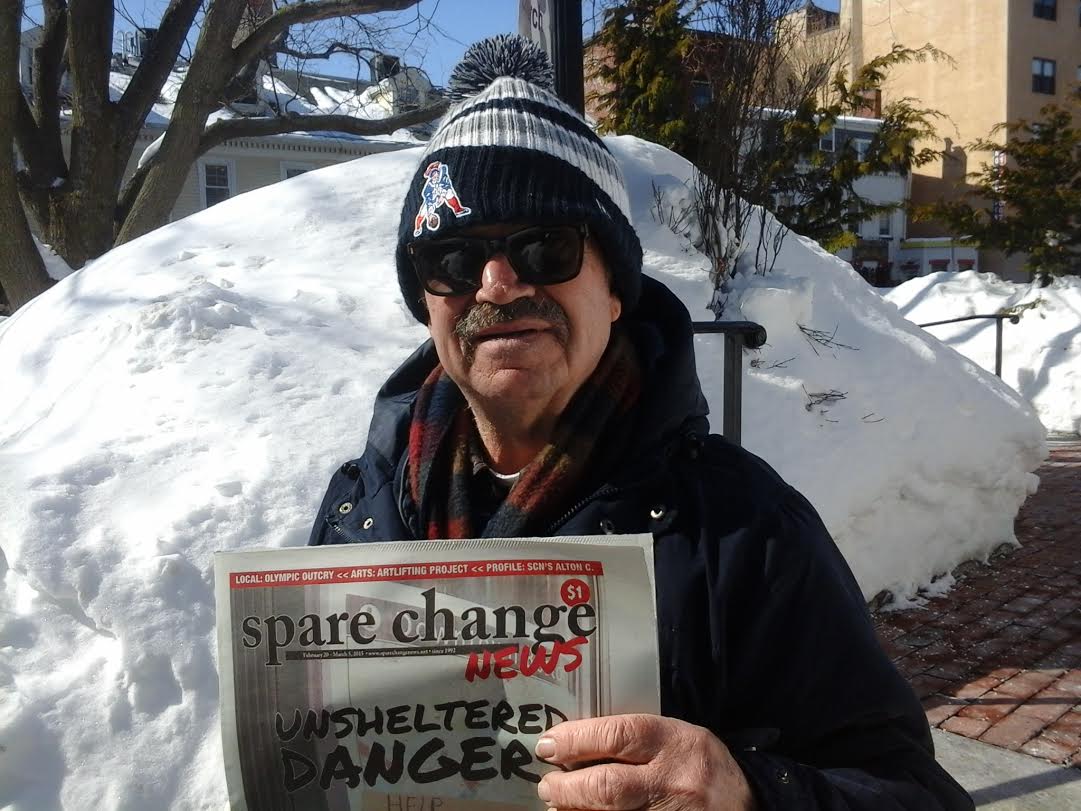

Joe retired from his job at the City six years ago and started working at Spare Change News two years later. At the wise old age of 73, Joe has been a lifelong resident of Cambridge. The newspaper certainly couldn’t ask for a better vendor.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.