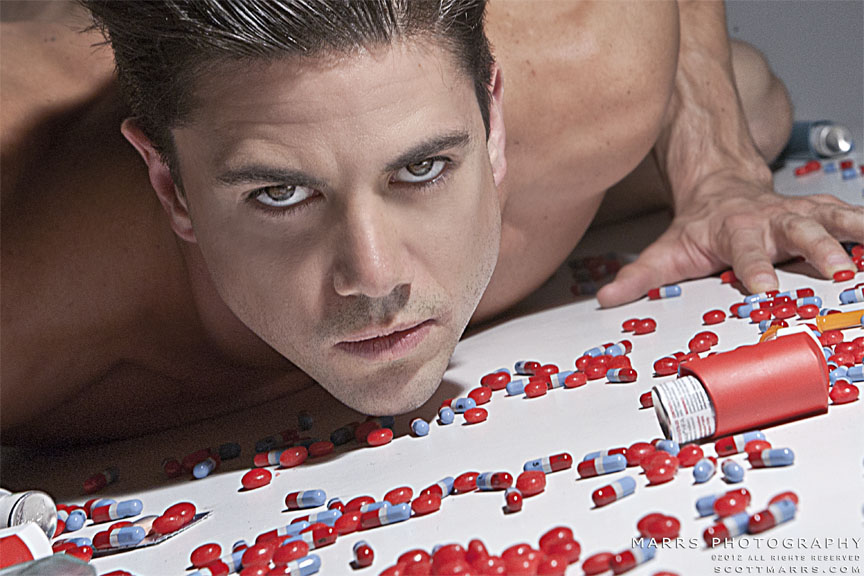

PHOTO BY SCOTT MARRS

Joe Putignano, a 38-year-old native of Brockton, Raynham and Bridgewater, is a former competitive gymnast who began the sport at the age of nine. He trained at the Olympic Training Center in Colorado Springs and later competed in the Junior Olympic National Championships at age 16. He performed in a long-running Broadway show and with the world-renowned Cirque du Soleil as a contortionist. Through it all, Putignano struggled with addictions to alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, heroin and prescription drugs.

After years of relapses and stints in therapy and rehab facilities, he’s now eight years sober and the author of a memoir, Acrobaddict. The book is about the connection between addiction and athletics, which he wrote in large part while touring with Cirque du Soleil. He’s currently at work on a second book and has aspirations to attend school to become a physician’s assistant. Spare Change News spoke with Putignano, now living in New York City, and he was open and candid about his life story, struggles with addiction and his road to recovery.

Putignano is scheduled to speak at Raynham on May 16. The event, held at the Raynham American Legion, is called “Learn to Cope” and is about his experiences with heroin addiction.

Q: When did you first start using?

I started drinking and using marijuana in high school, like a lot of kids. My parents owned a bar in Avon and I knew from an early age that they had problems with alcohol. I used to go the bar after gymnastics practice and I knew everyone there. It seemed normal to be around adults and alcohol. I would do my homework and stay there until it closed. A drink seemed like a normal thing. Being in a very competitive sport like gymnastics, your one goal is to get to the Olympics and I was starting to see that dream slip away, because I was already abusing alcohol and marijuana. I think I transferred my competitive and coping skills that l learned in gymnastics to drinking and using drugs. That drink made me feel human, you could just be “you.” I loved it right away. My gymnastics coach would pull me aside and he was aware of my problem because I would show up to practice hungover and smelling of alcohol. He told me I had a gift, and I was screwing it up, but I couldn’t stop. I wanted to, but I couldn’t.

Q: After you abandoned competitive gymnastics, what did you do?

I graduated high school in 1995, and I had discovered the rave scene in Boston when I was about 17. I discovered ecstasy and was also abusing acid and prescription drugs that I bought on the street. I wanted to go college, but I didn’t get in because my grades were so bad due to all the school I’d missed from all my gymnastics training. I decided to go to community college, where I coached gymnastics, but during this time my drug use had really escalated. After a year there, I got into Springfield College, and a gymnastics coach that I knew there said I could join the team. I thought, great, I’m going to change my life, no more drugs! And I did try for the first month, but then I discovered cocaine and was dating a cocaine dealer, who got me as much cocaine as I could ever want. And again, everyone around me knew about my drug use.

Q: Did you seek formal treatment given how serious your problem had become?

I showed up to a major college gymnastics competition while I was still tripping. I told my coach I couldn’t compete and that I had a drug problem and needed help. I said it but don’t think I meant it. My coach sent me to someone to help me and they gave me a choice, which was to go to a rehab for 14 days. I hated it and I lasted three days. The college wouldn’t take me back unless I enrolled in some kind of treatment program, so I went to an outpatient program, but I manipulated my therapist into prescribing me Klonopin because I was having trouble sleeping and I was getting high doses of it. Eventually, the school kicked me out, and I completely quit gymnastics because it was getting in the way of partying.

Q: Tell me about the period when you were homeless.

After I got kicked out of schooI, I had no place to go. My parents wouldn’t take me back home, they knew about my drug problems and I was stealing—anything to get drugs. I stayed in parks in Springfield. I stayed with dealers. I tried to stay with my parents here and there, and I was in and out of rehabs and psychiatric hospitals and had even been to jail. I also stayed in men’s shelters.

Q: How did you end up in New York City?

Q: How did you end up in New York City?

At that point, I was in my early twenties and I was ready to stop most drugs—I learned to manage my disease and become a functioning addict. I stuck to alcohol and pot. I lived in New Jersey and waited tables on the Upper West Side, and I was trying to go to 12-step programs. But then I got into heroin. I was working at the New York Times as a clerk and a writer for different departments. I would try to write the weather poetically, completely high out of my mind. But this company was great, and they helped me to get into my last rehab.

Q: Tell me more about Oatmeal and what he has meant and means to you?

Oatmeal, my teddy bear, was definitely my link back to my childhood. I got Oatmeal when I was little and, like most children with teddy bears, I took him everywhere—gymnastics competitions, etc. As I got deeper into my addiction, I believe I clung to Oatmeal because it symbolized my innocence and reminded me of the safe, loved, child I used to be. As I got deeper into my addiction, Oatmeal became my only link back to sanity and, in a way, he resembled hope and reminded me that I was once “a good person.” He was with me when I was homeless and living on the street and I still have him. His image is tattooed on my calf.

Q. How did you become part of Cirque du Soleil?

I had a therapist at the last rehab I went to a few years earlier who said something that changed my life. I can’t remember what exactly but something about how I was special and that if I wanted my life back, I would have to eat it, and it ignited some passion and inspired me. Right after she said it, I started to do handsprings and handstands in my room. I realized I could do gymnastics because I loved it and I could throw the Olympics out of the mix and just perform. I started training again and I met someone who performed with Cirque du Soleil. I went to Las Vegas to see them perform and I was jealous. But I realized that maybe I could do this. I was clean and sober and still working at the Times, and I Googled how to become a contortionist. I trained with a contortionist for a while and then started doing it on my own. I performed in a Broadway show, The Times They Are A Changin’, for two years, then at the Metropolitan Opera House. I met a producer with Cirque du Soleil, who approached me about a new show he was doing. It was created around a character called Crystal Man, based on my life. I performed with them in the show Totem for about two years, then I injured my shoulder.

Q: You’ve gone through a series of surgeries in sobriety. Has it been difficult to remain sober while going through so much pain?

In 2013, I had shoulder surgery. I’ve actually had shoulder and ankle surgeries in the past few years. Surgeries have definitely been stressful on my sobriety and I hope the CNN piece I did teaches others about sobriety and surgery. I have to say, it was a lot easier knowing Dr. Sanjay Gupta was rooting for me, because he is someone I deeply admire, and it’s nice to have a support group who wants to see me succeed.

I know many people in 12-step programs who relapse over small dental or surgical procedures because of the pain or opiates given after treatment. I opted for non-narcotic pain killers for my surgeries but I needed to do this, not only for my own sobriety, but to find new ways to address the over-prescription of narcotic painkillers. I’ve found Neurontin, Tylenol and acupuncture to be helpful alternatives for pain management.

Q: What’s been the hardest addiction for you to recover from?

Being a heroin addict is one of the worst things I’ve ever experienced in my entire life. It’s a full-time job. You’re sick the next day without it and it’s so expensive. I’ve overdosed on it. I was absolutely broken as a human being when I was on heroin. There was nothing left. Heroin is so addictive because it’s such a powerful painkiller, and it really filled all the places that I held pain—emotional, physical and spiritual. I wanted to die but I thought of my family. I knew the end was near, but I had the awareness to try one more time to get help and go to rehab, with the help of the New York Times, where people were incredibly helpful and supportive to me.

Q: How did you get into writing and who have been some of your influences in terms of writing your memoir?

I had always wanted to be a writer since age 11 and I’ve always kept journals. I met someone who encouraged me to write about my story. I started working on my memoir while performing on Broadway, then I re-visited it while on tour with Cirque du Soleil. I just want to be able to help people and tell them to keep trying to get sober, and say, If I can do it, so can you. I read and really liked two memoirs about addiction—The Basketball Diaries by Jim Carroll and Dry by Augusten Burroughs.

Q: How difficult was it to revisit the dark days of your addiction in Acrobaddict and then with the press tour after the book’s launch?

Writing Acrobaddict was very difficult to do because I not only had to revisit the emotions and despair that stem from addiction, but I had to look at all the terrible things I did to others in great detail. It was humbling and painful, but I knew in my heart that I wanted to get my story out there to help others. If my past can help someone else, then I did not live it in vain.

Q: What are you doing now?

I’m working on my second book, but it’s not about me this time. It’s a horror fiction novel. I’m also working on getting into school to become a physician’s assistant and taking prerequisite courses for that. I’ve been completely clean and sober since March 2007.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.