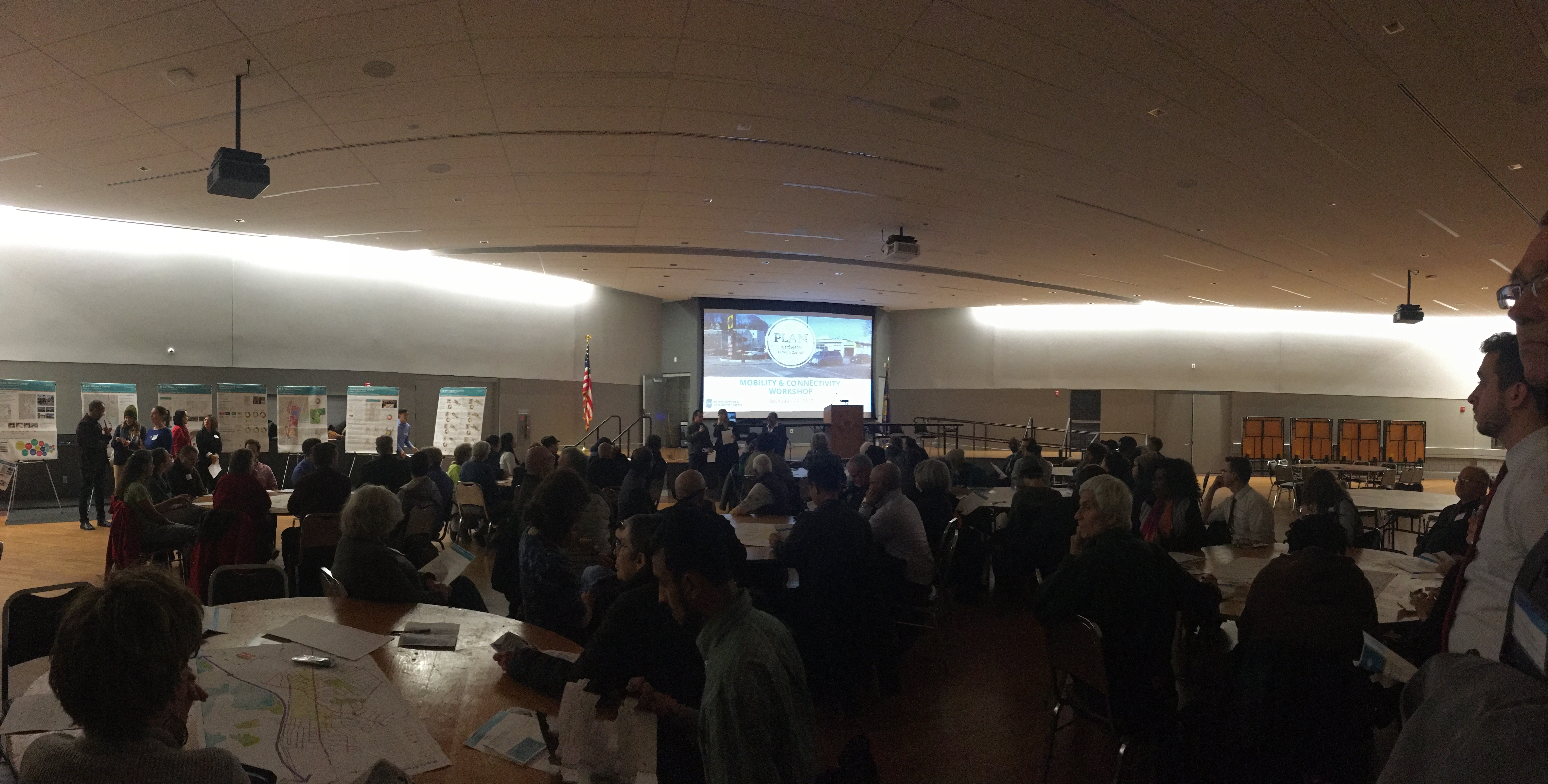

A City-led community meeting in Dorchester on the ongoing plan to redevelop Glover’s Corner took an unexpected turn on Wednesday night when local anti-gentrification activists interrupted the proceedings. But responses from a key city official and City Councilor Frank Baker following the protest provided some mixed signals in terms of how the group’s demands are being received.

It all started as a staffer for the Boston Planning and Development Agency (formerly the BRA) was wrapping up a slideshow about the City’s aim to improve transportation through the Glover’s Corner redevelopment plan. Then, seemingly without any city officials noticing, a young Vietnamese American activist from the area stepped up and began speaking into a mic. As she spoke, her fellow activists from the group, Dorchester Not 4 Sale, formed a large semicircle at the front of the room and held signs with phrases such as “Dorchester: You Have a Right to Remain.” The young woman explained her concerns that development, if done wrong, would push out those who had built the community.

Her fellow activists followed suit.

“If you really care about Dorchester, you’ll really listen to the folks who are in this room and the folks who are standing up here now,” another protester said.

While Wednesday night’s meeting was specifically focused on the issue of transportation, it was just one part of a larger initiative to completely re-do the Glover’s Corner area. Mayor Walsh first announced the Glover’s Corner redevelopment study early last year, and it was officially kicked it off this January—starting with a public commentary period and then followed by several City-led workshops to engage local residents in the process.

Despite these opportunities for public input, Dorchester Not 4 Sale said there is a deeper reason for their frustration—and for their suspicion that the BPDA’s gestures toward community consultation might turn out to be more symbolic than substantive.

The fledgling activist group first formed this summer, beginning with a series of potluck dinners to discuss the pressing threat of economic displacement in a city notorious for its increasing economic disparities and ever-rising rents. The group’s first concrete step was to send a letter to the BPDA in August. They noted that they were “excited about positive developments that could happen in Dorchester” but cited their concerns that the BPDA planning process “may further racial disparities, result in the displacement of current residents and negatively affect the diversity and community here.”

This particular issue has been publicly debated in Glover’s Corner because, while much of the area currently consists of parking lots and industrial-type lots—meaning development there could potentially increase the housing supply and help alleviate Boston’s rising housing prices—there is also concern about a domino effect occurring if large, high-end developments change the market overall. The upcoming Dot Block development, backed by billionaire real estate investor Gerald Chan, is one example locals have pointed to as the embodiment of their fears.

Dorchester Not 4 Sale also made two key asks in the letter: a six-month moratorium on the Glover’s Corner planning process to better assess its potential impact; and more detailed data and data analysis regarding the project’s various impacts (including housing, demographics, jobs, small businesses and the environment) to improve decision making. The group escalated matters to a protest Wednesday because they said that even after meeting with BPDA staff in October, they did not receive an answer to their demands—nor did they receive a response to a follow-up letter they sent in early November.

After the protest, I caught up with Lara Merida, deputy director for Community Planning and one of the meeting leaders, to ask for her response to these claims. She said that while the BPDA does provide relevant community data on its website, Dorchester Not 4 Sale is requesting the raw data and data analysis—something which Merida says BPDA has not yet completed.

“But we are going to get it to them and continue working with them,” she promised.

Activist Mimi Ramos responded to this promise after the meeting, telling me, “Maybe they should communicate that they are getting the data [to us]—and on a real timeline. Because the planning process hasn’t slowed down at all while we’ve been waiting [on the data].”

What’s more, some of the comments from city staffers on Wednesday night could be seen as underlining such concerns. The Glover’s Corner community workshops have featured group exercises ostensibly meant to help residents illustrate their hopes for the neighborhood. In an October workshop, attendees placed different colored blocks on large maps to show how they wanted the area’s land use to be divided among various uses. On Wednesday, BPDA senior planner Viktorija Abolina presented the results of that exercise, translating the general areas of consensus from the blocks/maps into a pie-chart visualization:

Pie chart derived from “block-on-map” exercise at a previous community workshop. Depicts attendees’ desired break-down of land-use in the area.

But Abolina also noted that these takeaways from the hands-on games were not promises. The pie chart, she said, “doesn’t mean it will happen [that way]—it means it will inform the conversation.”

But for activists like Ramos, guarantees are important. She says that she had to leave Fields Corner, where she was proudly born and raised, and move to Fall River for four years due to rising rent prices. She was only able to return to Dorchester recently because of a personal connection with a landlord who kindly kept her rent well below market rate. “It’s personal,” she said. “And it’s about the community and those we represent.”

Merida did express sympathy with the group’s underlying concerns. After trying briefly—and unsuccessfully—to get an activist to shut down the protest, she waited until the group was done.

“I think we’re here all for the same reason and I know workshops are tough … and I know that we are still working to get data to you,” she said to the group. “So I think what we need to do is to keep having these conversations together … and we all have the same goal of wanting to make sure we’re making an equitable neighborhood that’s right for everyone and gives people choices.” The protesters, however, remained frustrated and walked out.

City Councilor Frank Baker, who was also in attendance, was less conciliatory. As Merida indicated that she would continue the meeting as planned, Baker cut in, saying he wanted to add his thoughts. He stressed the value he saw in developing an area that currently has large swaths of parking lots and industrial areas—rather than residential places. Then he turned his attention to the protesters themselves.

“I just want to make sure that the people that care about this project stay involved and keep coming back. I don’t really know what just happened. I apologize for anybody that was trying to be here, like myself. We’re working, we’re working here.” His remarks were met by applause from those remaining in the hall.

As for the moratorium requested by the group, Merida and Baker seemed to be on the same page. “A moratorium is tricky because we’re all trying to learn from each other,” Merida said. “I wouldn’t want to have a moratorium on talking.”

Baker told me, “As far as I’m concerned, it’s not a valid request.”

This article originally appeared on elizadewey.com.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.