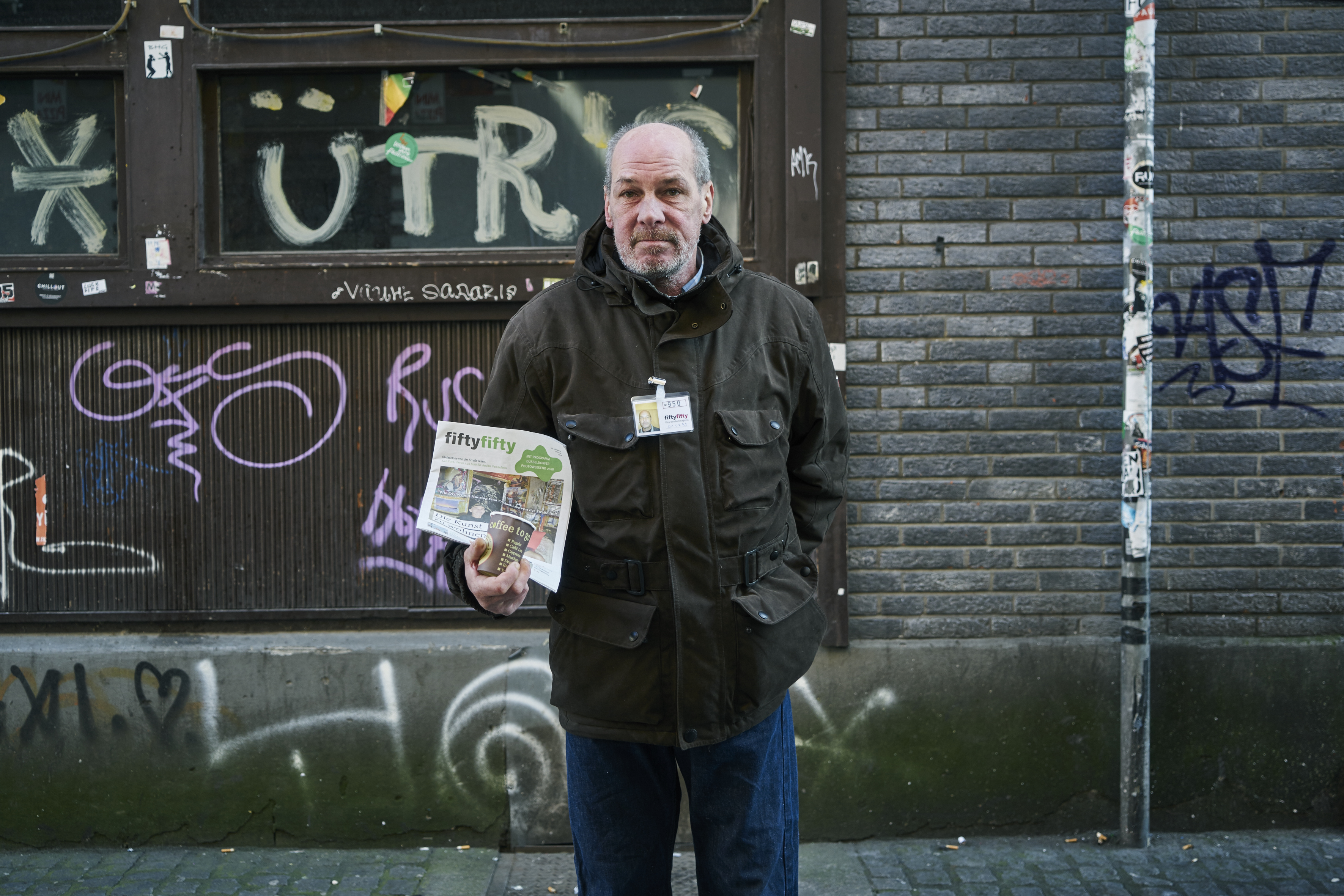

Karl Heinz on the streets. Photos by Frank Schemmann, Getty/Havas

Clothes make the man, and the vendors over at fiftyfifty, a fellow street paper, had the chance to experience this principle first-hand as the subjects of an unusual photo shoot. Advertising agency Havas collaborated with the world’s leading photo agency Getty Images to create a completely new perception of people living on the street, with the aim of helping to challenge existing prejudices. Their campaign, Repicturing Homeless, has received media coverage all around the world.

Can images and film achieve change? The answer, according to renowned Italian author and film director Pier Paolo Pasolini, appears to be yes, but incrementally at best: “Trying to have an impact on people is a bit like trying to scoop out the ocean with a thimble.” Advertising expert Darren Richardson, who together with his team at Havas was responsible for the idea of Repicturing Homeless, does not believe that “photos can solve an issue like homelessness,” but he maintains that they can at least promote “scrutiny of visual stereotypes.”

“Scrutiny” is an understatement – there’s far more to it than that. It’s ultimately about contemplating what makes us human, the meaning of status symbols, and how mercilessly we are reduced to such symbols by a society defined by power and conspicuous consumption.

Long before humans tapped their endorphin spigots through social media sourced validation, Pasolini coined the phrase “hedonistic fascism.” This phrase appears in Pasolini’s visionary work “Corsair Writings,” and is generally interpreted as a form of greed so pernicious that it leads to the brutal oppression of both individuals and society as a whole.

According to Pasolini, we suffer as individuals if we allow ourselves to be defined by prescribed patterns of consumption – the poor because they dream about what they neither have nor really need, and the rich because they have a compulsive desire to possess things which, although costly, are existentially meaningless. Ultimately society as a whole suffers, because it allows its vision and values to be dominated by inane advertising for things we neither need nor want until we’re told we do.

Pasolini wrote an essay – world famous in his time – regarding a clothing manufacturer’s blasphemous slogan: “Thou shalt not have any other jeans but me”. He once, in a different context, summarized the situation as follows: “the real anti-democracy is mainstream culture”.

Ironically, Repicturing Homeless was created by an advertising agency whose purpose, like all agencies, is to expertly arouse the obsessive desires of target markets around the world. And yet, Repicturing Homeless provides a new perspective not only on the losers of Capitalism, but also on ourselves. Who are we when we have no things left? This probably isn’t a concern often discussed within the advertising industry.

Repicturing Homeless addresses fundamental questions concerning our sense of self, and how deeply entangled our self worth is with consumerism.

This question may resonate, for example, when formerly homeless Kalle sees himself in the mirror wearing business wear, designer glasses, and a luxury watch, and breaks down in tears.

Kalle.

This fiftyfifty seller, 56 years old and an alcoholic, languished on the street, on the bottom rung of society, for over 20 years before recently – finally – receiving a flat as part of this street paper’s Housing First program. In between sobs, he confesses: “I feel like a new person.”

Jennifer’s waitress uniform is far less luxurious, but she’s beautifully groomed nonetheless. While waiting around in the posh hotel where the photo shoot is taking place, a senior member of the hotel staff reprimands her, asking whether she has nothing better to do than stand around gawking. He’d assumed she worked at the hotel.

“That’s when I first realized just how big a part clothing plays,”Jennifer said. “It shows what I could be. But it takes more than just clothes. Even in an outfit this fancy, I still wouldn’t get by in a meritocracy.”

Karl-Heinz Hasenjäger, also 56, is in a similar situation. He was “born on the street,” he says, and his parents were homeless before him. Karl-Heinz was photographed as a fashion designer and he found the new role a surprisingly good fit.

“Somehow, they’ve recognized the creative core in my personality,” the talented amateur painter explains.

But real life has not been so kind to him.

Karl-Heinz currently lives in a shabby shelter, light years away from a life as a recognized creative force. He enjoys this dream of a better future so much, and yet he is so imprisoned in his own small world – which he bears with a singular sense of gallows humor. Having a realistic understanding of his position and finding a certain satisfaction in it is his “own way of coping,” he says. He stays humble, and keeps working even when prospects are thin on the ground; He resists the urge to give in to desperation, and always has a strategy for surviving.

The same can’t be said for Michael Hermann, whom everybody refers to as Hörman. Visibly scarred by life and now living in a fiftyfifty flat after more than 20 years under bridges and on the street, he still harbors lofty dreams. Fittingly, the creative team at Havas and photographer Schemmann saw a professor in him: decked out in expensive clothes and proudly striding around the set, he plays the role perfectly.

Although Hörman himself admits that it couldn’t be much further from his own reality, he remains hopeful.

“Life is full of surprises,” he murmurs from behind his red beard, as he writes Einstein’s famous formula onto a window for a photo. Could Einstein be his alter ego? Hörman hopes that it might one day be possible to overcome the constraints of a fate characterized by dependence on drugs and other pitfalls.

A different perspective on yourself is something that self-awareness can provide, certainly, but first and foremost something is revealed by the way your environment responds to you. And this is exactly why it’s not just the costume that has the impact – it’s also the act of documenting the transformation the costume facilitates in photographs.

Thirty-six-year-old Vanessa has been homeless for over a decade, and says it’s the disparaging looks she gets while selling her street paper that make her feel discriminated against. She can use the photos that she’ll now keep on her cheap mobile phone to get the message across to people: look, this is me as well. She’s more than just the woman on the street, whom conceited fellow human beings dart past with unkind judgement on their lips: “Get a job!”

Vanessa on the streets

Time and time again, this patronizing demand assaults her ears, as if selling a street paper wasn’t work simply because it’s not seen as proper, acceptable work by much of society. That’s something Vanessa has only experienced once in her life – and even then it was only a feeling she got while posing at the photo shoot for Repicturing Homeless.

What the images captured at the shoot are capable of conveying does have value to society. Vanessa realized that this was the case after the media suddenly started to show an interest in her, asking her over and over to retell her life story. The attention is benefiting her, because Vanessa, much like other people condemned on the street, is suddenly able to use her visual transformation to help present a lesson about the dangers we all face in this post-fact, capitalist society. Vanessa and the others hold a mirror up to all of us. Look out – the same thing could happen to you in this predatory economy. We could all stumble.

Vanessa during the photo shoot.

“Instead of clichéd, conventional images of desperation and poverty, we’ve tried to surprise people and encourage them to think with our campaign,” said Darren Richardson, Chief Creative Officer at Havas. “Our approach is not intended to leave people downcast or with a heavy conscience – first and foremost, we want to prompt people to challenge their perceptions of our fellow human beings, influenced as these ideas often are by privilege.”

“We believe that the photos have the power to change perceptions, even inspire compassion, drive changes,” said Paul Foster, Senior Director at Getty Images. In other words, images can achieve change. This means, according to Foster, that the Repicturing Homeless project will directly benefit the disadvantaged people that fiftyfifty looks after. Getty Images will donate all proceeds from the sale of the photo licences to magazines, newspapers and websites, to fiftyfifty housing projects for the homeless, ensuring that these images have an impact.

Social marketing

fiftyfifty has launched a large number of lucrative social campaigns over the years – some of which have received coveted design awards – with the aim of communicating the scandal of poverty in a modern way. Our partners are the agency in puncto, responsible for the layout of the issue Repicturing Homeless appears in, and the design of our home page.

One of the things we have achieved together with in puncto was to secure a cinema spot for Russian street circus Upsala. In addition, a tram completely designed in spectacular fashion by in puncto is set to ride through Düsseldorf in the near future. Students at the University of Applied Sciences Düsseldorf (HSD) and private higher education institutions such as the AMD Academy of Fashion and Design have canvassed on behalf of fiftyfifty, as have many students from the Lore-Lorentz-Schule Düsseldorf vocational college and several top international agencies like Jung von Matt, McCann Erickson and even Havas, which was responsible for the design and implementation of Repicturing Homeless.

Some of the other sensational ideas Havas has produced for fiftyfifty include making a homeless person literally invisible on the street using light effects, lowering the temperature in a cinema to the level of an average fridge and then show a film about the cold on the streets, including verbatim quotes from homeless people. They also won the country’s leading competition for large posters (BEST 18/1 Award) with an intelligent social media campaign, winning the prize money of EUR 50,000 on behalf of fiftyfifty in the process.

A visual résumé of our most important social campaigns can be found in the fiftyfifty archive in a special publication by the University of Applied Sciences Düsseldorf: http://www.fiftyfifty-galerie.de/archiv (scroll down to 2012) and on the fiftyfifty video channel – a link to which can be found at the very bottom of our home page alongside the YouTube logo.

Translated from German by Alex Green

Courtesy of fiftyfifty / INSP.ngo

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.