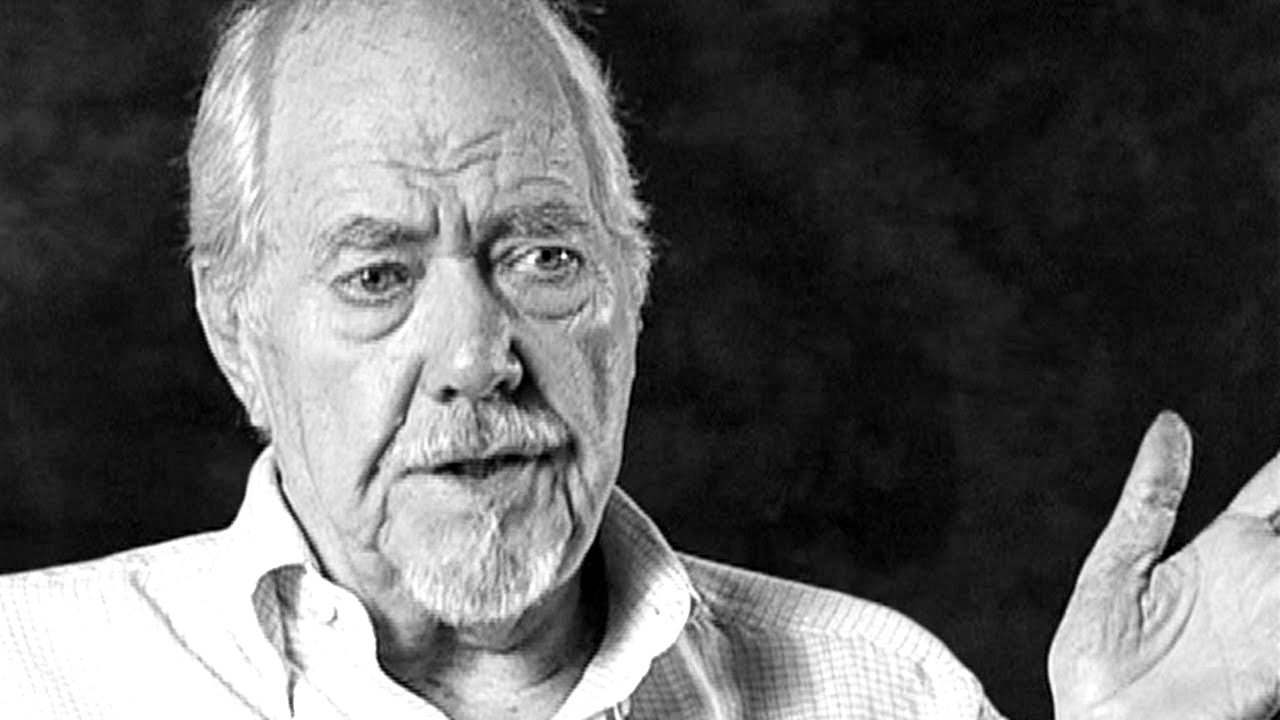

In an age when multimillionaire matinee idols like Johnny Depp and Christian Bale are trumpeted as Hollywood mavericks, the career of the late director Robert Altman may call for stronger words. Today’s profit-minded artist-moguls might just call him crazy. Even in the ‘70s, that golden age of maverick Hollywood, Altman baffled fans and disturbed the powers that be.

Through a 40-plus-year career, he lost the studios untold millions, never stopped making movies and had more comebacks than Bob Dylan. He was also more innovative and stubbornly idiosyncratic than anyone in Hollywood.

Starting in June, the Harvard Film Archive at the Carpenter Center for Visual Arts in Cambridge has been presenting the complete Altman movie career over a three-month period. It’s been almost nine years now since Altman’s death, so it’s a perfect time for an exhaustive career retrospective: a time for tempered respect and honest assessment of the man who was among the most dazzling, unorthodox, frustrating and intractable visionaries of cinema history.

Fully two-thirds of his movies might be deemed outright failures, yet he is still an unassailable giant of cinema. His every film is Altman-esque.

The first time I saw Altman in person he was speaking in front of a large audience at Tufts, soon after he’d completed filming on Nashville.

He looked at the crowd. “I’ve never done this type of thing before,” he says.

“Are you nervous?” asks the moderator.

Altman looks at him as if he is daft: “When I have a meeting with a studio head, and my last film has lost the guy millions, and I have to ask him for many millions more for my next film … that makes me nervous. This here is easy. Nothing is on the line.” And he smiles his killer grin.

Though Nashville and MASH are more famous, my vote for THE Altman masterpiece is 1971’s McCabe & Mrs. Miller (screening on 8/15). Like much of Altman, it is a subversive twist on a genre: in this case, heroic westerns. It’s a bitter, snowy northwestern, with a deluded gambler “hero” (Warren Beatty) whose great American dream is to build a classy whorehouse in a woebegone mining town. Julie Christie is Mrs. Miller, a world-weary madam, whose opium addiction sabotages any chance of enduring romance with McCabe.

Altman never reached McCabe’s state of elegiac grace again. With dreamlike cinematography by Vilmos Zsigmond, a mournful soundtrack of Leonard Cohen songs, a brilliant cast and, rare for Altman, a tight script, it’s on my list as one of the greatest films of all time. A revisionist western of the highest order, it stomps on American manifest destiny mythology, creating a tragic, eloquent aura perfect for the Vietnam era: a time when our national guilt produced some haunting cinema. It’s also one film that can only be fully appreciated on a big screen and with a mint-print, for the subtle color-scheme turns to mud with poor prints.

Altman never gave the audience, or the producers, what he thought they wanted, and sometimes he got away with it. He emphasized atmosphere and character over story, languor over tension, multi-tracked overlapping dialogue that could be hard to discern, and a penchant for small, odd moments over big plots. California Split, (7/10), one of his antic best, was about gambling in Vegas, yet the plot did not depend on wins or losses. It was all character and atmosphere. The extras were real-life gambling addicts.

I remember, in 1976, the shock of seeing his follow-up to Nashville: a bizarre dog of a movie, the genre-busting Buffalo Bill and the Indians; or being appalled by losers like A Perfect Couple, O.C. and Stiggs or Dr. T and the Women. Some films were even deemed unreleasable. I understood why he was called misogynistic, though great actresses loved working for him. The better word may have been misanthropic. In 1978, I was at a press conference with Altman after a screening of A Wedding, a harsh, ultimately dreary satire.

“My type of comedy,” he says, “is the kind where the laugh sticks in the audience’s throats, and they begin to gag.”

That kind of giant ego got Altman into the pantheon of greatness and also paved the way for a lot of daring failures. He worked into his ‘80s in TV and theater when movies wouldn’t back him anymore. He “came back” big-time with The Player in 1992 (7/30) and made two of his most likable films, Gosford Park (8/16) and Cookie’s Fortune (8/9) in old age. Yet he was nervy and strange enough to make Kansas City –– a film set in the jazziest, most outlaw legendary city of the 20th century, the city of his own youth— — and he still managed to make it dull and inert. I guess he never met a legend he didn’’t want to knock down. His like will never be seen again.

The dreamlike, the surreal, the too real, the seriously kooky –– here’s some lesser- known Altman worth watching: Brewster McCloud, 3 Women and The Long Goodbye.

The Complete Altman includes astonishingly obscure low-budget early work, filmed plays, and “juke-box” shorts with stripper Lili St. Cyr and songwriter Bobby Troup.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.