As you’re probably aware, a controversy is raging in the United States right now over the vaccination of children. Some parents have been refusing to vaccinate their children against diseases like measles because they don’t trust the medical establishment, while others have been refusing based on their religious beliefs. Some people have even blamed a recent measles outbreak at Disneyland on these anti-vaccination parents.

Here in Boston, a city of historic firsts, this is old news. Boston experienced its first vaccination controversy nearly 300 years ago. At the time, the disease in question was smallpox, which was a scourge in the Colonial era. Far more deadly than measles, smallpox also caused disfiguring pus-filled sores.

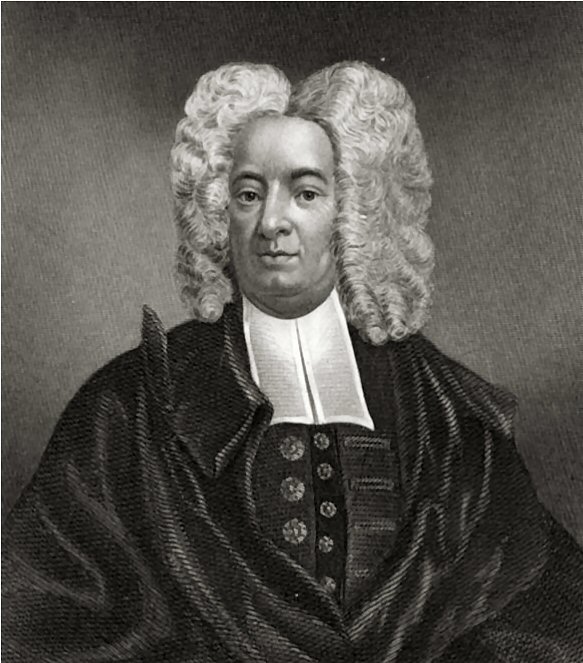

The man at the center of the controversy was Zabdiel Boylston, a prominent and wealthy Boston physician. Boylston lived a respectable and uncontroversial life until May, 1721, when he was summoned by the Rev. Cotton Mather, Boston’s leading Puritan clergyman. Mather explained that three sailors with smallpox had been discovered in Boston. While the city always tried to quarantine disease carriers on the Harbor Islands, the infected trio had somehow slipped through, and an epidemic was coming.

Mather was interested in science and had recently learned from his slave Onesimus that certain African communities could prevent smallpox through inoculation. They made incisions in the arms of healthy people and rubbed small amounts of smallpox pus into them. Anyone who was treated this way developed very minor symptoms before becoming immune to the disease. Mather wanted Dr. Boylston to combat the epidemic using this technique.

Boylston agreed. Immediately, he inoculated his own teenage son and two family slaves. The procedure was successful and he proceeded to inoculate patients outside the family. Controversy erupted, however, when the citizens of Boston learned about the doctor’s activities. Not understanding the science behind inoculation, they believed he was deliberately spreading disease.

Many of Boylston’s fellow physicians agreed. There were no formal medical schools at the time and most doctors learned their trade from their fathers. This new form of treatment sounded unorthodox and dangerous to these traditionally trained physicians. Adding to the panic, one of the city’s newspapers published an editorial arguing that Boylston was tampering with God’s plan and that God might send something even worse than smallpox as punishment.

The local clergy, who were well-educated, tried to calm the populace but to no avail. An angry mob formed and roamed through the streets with a noose, looking to hang Boylston. They invaded his home, but, luckily, Boylston was safely hidden. Protesters later threw a grenade into his house, but it did not detonate.

Wearing a disguise and working by night, Boylston continued his inoculations, eventually treating 244 people. Six of them died, but it was a small percentage compared to the 14 percent of non-inoculated victims who perished that year (844 deaths out of 5,980 cases). Inoculation worked.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.