On the same day the USOC announced that they decided to pull the bid for the Boston 2024 Olympics Games, No Boston 2024, a grassroots organization sent the public a newsletter, entitled “We won! But the fight continues.”

“We were fighting the Olympics because we wanted a Boston that works for all residents, a city rooted in values of justice, democracy, equality and sustainability,” the newsletter states. Indeed, at the very beginning of the Boston 2024 campaign, many tactics were exposed which could be hardly ignored by the general public: numerous behind-the-door meetings among the key players, undisclosed emails between city officials and back-and-forth negotiation with the Boston neighborhoods about possible ventures are probably among the most prominent ones.

For all the local activists who opposed the bid, the larger fight may still continue, but the victory was theirs on Monday, July 27.

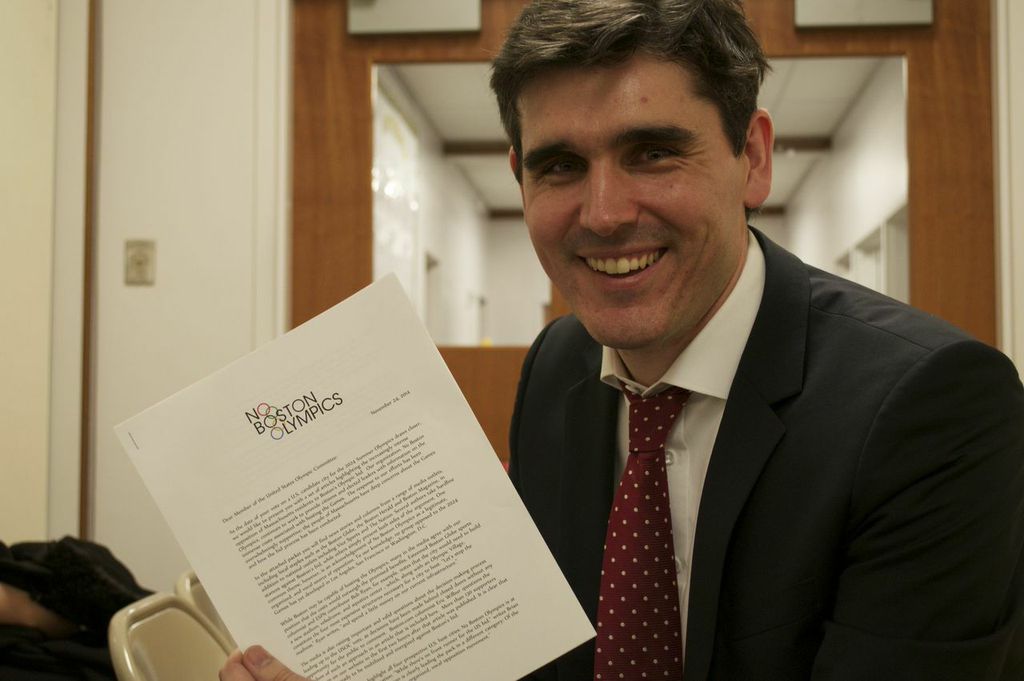

“It’s very much a relief,” says the co-chair of No Boston Olympics, Chris Dempsey at the celebration party in Boston’s Beantown Pub.

One of the Boston 2024 supporters posted on Facebook, “And with that Boston’s half-assed bid to host the Olympics is over. Hopefully, a more serious/mature groups takes it on next time.” Yet, many may wonder how an organization formed by several local residents, such as No Boston 2024, could possibly defeat someone who has tens of millions of the dollars?

Even at the beginning of the Boston 2024 campaign, a poll conducted by WBUR showed that over half of Boston’s residents supported the Olympics. It only began to steadily decline after the USOC chose Boston as the host city. “Then they [general public] learned that the USOC required building three venues from scratch, and taxpayers will be on the hook for overruns, and all these requirements you have to meet from the IOC,” Dempsey says.

“The more people learned about the Boston 2024 bid, the less they liked it,” Dempsey continues, explaining why the polling showed a decline in support from the public. Remember the barrage of the criticism drawn from the public last October? President of the Boston 2024 Partnership, Dan O’Connell told MassLive: “We don’t see a separate Olympic park as they have done in some cities. We think of Boston as the Olympic park. It’s the Common, it’s the Greenway, it’s the Waterfront, it’s the Harbor.” For example, Boston Common was first proposed as the location for beach volleyball. Imagine what would it be like to have a bunch of scantily-clad athletes fiercely competing near the dead bodies of Samuel Sprague and others who fought in the Revolutionary War.

Last November, a few months before the historic snowstorm hit Boston, a small group of people gathered in Jamaica Plain demanding that Doug Rubin hold public meetings. Rubin is a founding partner of Northwind Strategies, a company that supports Boston 2024’s bid. Rubin then promised a public meeting “very shortly,” but did not give an exact date. At the gathering, Rubin also declined to comment on the issues of affordable housing and displacement. Erin Murphy, executive vice president of Boston 2024, told local media that she saw the Olympics as Boston’s future legacy.

“Very shortly” turned out to mean two months for Boston 2024. In those two months, city officials were blamed for failing to provide Boston residents with convenient transportation. Snow piled up in neighborhoods and wasn’t cleared in a timely manner, especially in those neighborhoods where people of color reside, such as Roxbury and Mattapan. Numerous reports showed that Boston residents stood in line during the storm for trains. These realities made Bostonians question if the city was even capable of hosting an international event like the Olympics.

A month later, another WBUR poll showed that support for the 2024 summer game had fallen sharply with only 36 percent of the respondents backing the idea. Steve Koczela, who conducted the live telephone survey between March 16 and 18, told WBUR that it was significant that Olympics support had continued to fall, even though the weather and operations of the MBTA, the area’s public transit system, had improved.

A post-win strategy for No Boston Olympics is finding common ground with their rivals, including Boston 2024. “Hopefully, we reach out to Boston 2024, sit down with those folks, have a conversation on how we can use the energy that’s developed from this conversation to redo something that’s better for our city long-term.” Dempsey talked to local media with a triumphant smile on his face while taking sips from his beer.

Dempsey has “friends and colleagues” on Boston 2024’s team, he says. And he believes that everyone on both sides wants Boston to be a better city. “We just have different visions on how to get there.” In fact, Rich Davey, the newly named the chief executive of Boston 2024, used to work with Dempsey when Davey was the general manager at MBTA, and Dempsey was at MassDOT.

That common ground, which Dempsey pointed out, includes creating more housing and investing more in the T. However, at this point, he’s still in the process of figuring out a time to converse with his rivals.

Currently, all the anti-Olympics organizations have moved on to new goals. On July 28, No Boston 2024 launched a new crowd funding campaign through MuckRock for communications from Boston Corporation Counsel, Eugene L. O’Flaherty. It’s reported that the group’s co-founder, Jonathan Cohn, tried to raise nearly $400, the amount it would take to disclose all the Olympics-related emails to and from Mayor Walsh’s chief of staff, Dan Koh. Cohn has received less than half that amount.

In terms of social media outreach, Cohn said they did a far better job than Boston 2024. They reached out to the former opposition of the Chicago 2016 Olympics. “There were people from Chicago who talked to us about the legacy of the failed [the Olympics] bid,” Cohn says. In 2009, Chicago was knocked out in the first round of IOC voting, and the Olympics bid went to Rio de Janeiro.

To Cohn, Mayor Walsh’s refusal to sign the host contract for 2024 Olympics was “just [him] trying to get ahead of what seems to be inevitable at this point.” In December, however, Walsh had said he would sign the host contract without reservation.

As all the people who opposed the Boston Olympics clinked their wine glasses, celebrating at the party, Dempsey’s summary of their campaign’s victory was simple: “We felt like we always had the facts on our side.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.