Horace Seldon was happily lying on his back, waving his hands and feet in the air the first time Shay Stewart-Bouley saw him.

Shay was just starting out as Executive Director of Community Change, Inc., the anti-racism non-profit Horace founded in 1968, and she was at the organization’s forty-fifth anniversary party. It also happened to be Horace’s ninetieth birthday. Shay was bemused, and perhaps somewhat alarmed, to hear someone call out, “Everybody do the dead fly!” followed by a number of people lying on the floor doing the same strange horizontal two-step as Horace.

“The Dead Fly Club was about doing inappropriate things at inappropriate times,” says Horace’s son Gary. Anyone who knew Horace was welcome in the “club,” for which the only membership requirement was doing the “dead fly” dance on command. Whatever the motivation – bonding exercise, way to blow off steam – the inherently goofy nature of the activity belies Horace’s sense of himself as someone who was called to the more weighty task of advocating for racial equality.

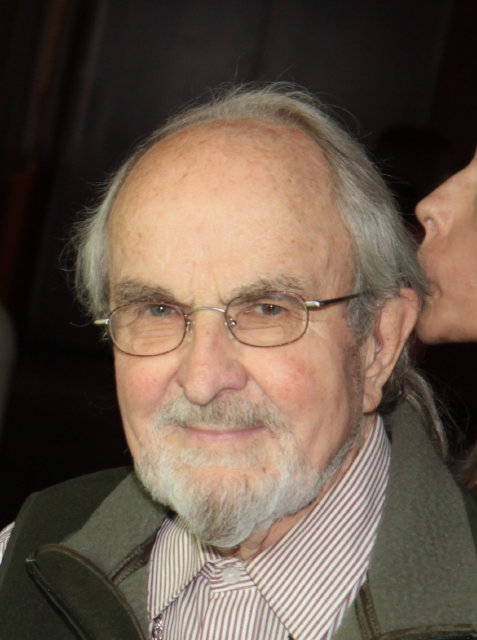

When Horace died in 2017 at age 93, he left behind a powerful legacy marked by numerous awards and honors, including having had Boston Mayor Marty Walsh declare June 18, 2017, Horace Seldon Day.

One could argue that this white man was not a likely candidate to take up the mantle of racial justice work. He was born in 1923 into a sheltered, comfortably middle-class life in Haverhill, Massachusetts, and his father worked as an insurance salesman. After Pearl Harbor, Horace joined the army and was sent to Iceland in 1943, where, far from the action, he had ample time to think about his future. He decided to become a minister, eventually going to Amherst College, where he majored in English and was president of the college’s New England Student Christian Movement.

In 1959 he settled in Wakefield, Massachusetts, with his wife and two young sons, and found work as a youth minister. But in 1968 Horace had an epiphany that changed the course of his life while driving on the Mass. Turnpike, near the Chicopee marker, of all places. It was a week after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and a few months after the release of the Kerner Report, the results of an investigation initiated by President Lyndon Johnson that detailed the ways racism and economic disparity led to civil unrest.

“I knew that I was to use the next years of my life to work on the ‘white problem,’” Horace wrote of this moment in his autobiography “No Longer At Ease Here: Trapped In A History. “I had no idea what that meant practically,” he wrote. “I knew only that I must do whatever was required.”

Horace’s radicalization led to an interior scouring, causing him to shed years of preconceived notions about race, gender, and class. His autobiography is riddled with moments of self-realization, or as he phrased it, “learnings.”

As an adolescent, he performed in a Minstrel Show sponsored by his church, covering his face with burnt cork and “widening” his lips with lipstick. Horace recalls the performance with surprising candor, and also some bitterness. “I learned how to forgive myself,” he wrote of this particularly racist, and painful learning experience, “but I have never quite forgiven the church for condoning that conduct.”

In the early sixties, while working as a youth minister, Horace organized trips to Roxbury for white high school students to work with black churches. One day a black member of the high-school youth council, who lived in Roxbury, pointed out that the white congregants coming in from the suburbs to help his community made he and his friends feel like “animals in a zoo.” After being put on display, they were left behind while the white spectators retreated to neighborhoods outside of the city.

This turned out to be another learning moment. “I was part of an institution, well-intentioned in its leadership, perpetuating relationships of power which made certain the continuation of the very forces which created the human frustration and anger I saw emerging in the city,” Horace wrote.

It was around this time that Horace experienced a tragic loss. In 1964 his wife, Sylvia, suffered a fatal asthma attack, leaving Horace to raise their two boys on his own. Losing Sylvia was devastating, but Horace continued to put the needs of others first.

He was admired for his honesty about how he had internalized racial biases, an admission that earned the respect of his colleagues, who looked to him for guidance. When Shay Stewart-Bouley took over the leadership of Community Change, Inc. (CCI), she had to learn to navigate the network of donors and volunteers who struggled to adjust to having a black woman at the helm of CCI.

At one point she found herself saying to Horace that she “could no longer make sense of this work.” Horace wrote her a letter, saying that he didn’t have the answers to her questions, but encouraged her to read the work of black legal scholar Derrick Bell. In his 1992 book, Faces At The Bottom of the Well, Bell posited that accepting the permanence of racism frees one from despair.

This marked a turning point for Shay. She realized that she could never alter human nature, and she’d be doing this work forever. Shay says she found the revelation liberating, noting that it was important to “Live your life in the struggle, and at the same time, you will live.”

Paul Marcus had an epiphany of his own after spending an afternoon with Horace, deciding then to give up teaching high school and volunteer with CCI. He took over as Executive Director of CCI when Horace stepped down after 28 years.

“When I first met Horace,” Marcus says, “he said his job was the pooper scooper of racial justice.” Behind this characteristically self-deprecating comment was a serious mission. Horace wanted white people to acknowledge and counteract the effects of white privilege. In the seventies CCI got involved in Boston’s school desegregation movement, and worked with other non-profits to reorient people’s perception of racism as personal to understanding it as a systemic and structural problem with society as a whole.

Later Marcus bought Horace an Egyptian scarab beetle from the gift shop at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. Scarab beetles roll seed-rich dung into balls that then function as tiny fertilizer bombs, helping to propagate new plants. Horace wore this apt talisman around his neck.

Horace inspired many people to strive for a better, more peaceful world—including his children. His son Gary recalls getting arrested in 1977 for protesting at the Seabrook Nuclear Power Plant in New Hampshire. When he was released after ten days, he came home to a house filled with friends and family cheering for him. His father had organized a party to celebrate his arrival. Gary’s other friends who were arrested, he says, were reprimanded for their activism. His voice breaking, Gary said that he “came home to a hero’s welcome.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.